Copulas and Sklar Distributions

This section gives some general definitions and tools about dependence structures, multivariate random vectors and copulas. Along this journey through the mathematical theory of copulas, we link to the rest of the documentation for more specific and detailed arguments on particular points, or simply to the technical documentation of the actual implementation. The interested reader can take a look at the standard books on the subject [1–4] or more recently [5–8].

We start here by defining a few concepts about multivariate random vectors, dependence structures and copulas.

Reminder on multivariate random vectors

Consider a real valued random vector

Recall that you can construct random variables in Julia by the following code :

using Distributions

X₁ = Normal() # A standard Gaussian random variable

X₂ = Gamma(2,3) # A Gamma random variable

X₃ = Pareto(1) # A Pareto random variable with infinite variance.

X₄ = LogNormal(0,1) # A Lognormal random variableWe refer to Distributions.jl's documentation for more details on what you can do with these objects. We assume here that you are familiar with their API.

The probability distribution of the random vector

For a function

Note that the range

Copulas and Sklar's Theorem

There is a fundamental functional link between the function

A copula, usually denoted

In this documentation but more largely in the literature, the term Copula refers both to the random vector and its distribution function. Usually, the distinction is clear from context.

You may define a copula object in Julia by simply calling its constructor:

using Copulas

d = 3 # The dimension of the model

θ = 7 # Parameter

C = ClaytonCopula(d,7) # A 3-dimensional clayton copula with parameter θ = 7.ClaytonCopula{3, Float64}(θ = 7.0,)This object is a random vector, and behaves exactly as you would expect a random vector from Distributions.jl to behave: you may sample it with rand(C,100), compute its pdf or cdf with pdf(C,x) and cdf(C,x), etc:

u = rand(C,10)3×10 Matrix{Float64}:

0.526499 0.021291 0.328704 0.378685 … 0.00930735 0.435106 0.639032

0.185059 0.0198878 0.327653 0.634566 0.0101885 0.314647 0.717941

0.230508 0.0245785 0.407804 0.440913 0.0122688 0.391426 0.831335cdf(C,u)10-element Vector{Float64}:

0.1799684597482713

0.018217998740626747

0.29288020390502756

0.36205242045170244

0.14000537176743774

0.2035742447106413

0.47338044958092873

0.008645801678165276

0.30242231253926444

0.6022595816237779You can also plot it:

using Plots

plot(C, :logpdf)

See the visualizations page for details on the visualisations tools. It’s often useful to get an intuition by looking at scatter plots.

To give another example, the function

is a copula, corresponding to independent random vectors.

This copula can be constructed using the IndependentCopula(d) syntax as follows:

Π = IndependentCopula(d) # A 4-variate independence structure.One of the reasons that makes copulas so useful is the bijective map from the Sklar Theorem [9]:

For every random vector

The copula

This result allows to decompose the distribution of

We can then leverage the Sklar theorem to construct multivariate random vectors from a copula-marginals specification. The implementation we have of this theorem allows building multivariate distributions by specifying separately their marginals and dependence structures as follows:

X₁, X₂, X₃ = Gamma(2,3), Pareto(), LogNormal(0,1) # Marginals

D = SklarDist(C, (X₁,X₂,X₃)) # The final distribution, using the previous copula C.

plot(D, scale=:sklar)The obtained multivariate random vector object are genuine multivariate random vector following the Distributions.jl API. They can be sampled (rand()), and their probability density function and distribution function can be evaluated (respectively pdf and cdf), etc:

x = rand(D,10)

p = pdf(D, x)

l = logpdf(D, x)

c = pdf(D, x)

[x' p l c]10×6 Matrix{Float64}:

6.69517 5.58109 1.17787 0.0017726 -6.33531 0.0017726

1.18882 1.10947 0.247609 1.71045 0.536758 1.71045

1.49555 1.10542 0.261395 21.8693 3.08508 21.8693

10.5131 36.1181 2.18118 2.15652e-5 -10.7444 2.15652e-5

5.49422 2.75962 1.18787 0.0368705 -3.30034 0.0368705

4.36807 2.5307 0.874563 0.0350585 -3.35074 0.0350585

3.79386 1.64029 0.826916 0.374565 -0.981991 0.374565

1.77016 1.17064 0.283964 3.74605 1.3207 3.74605

1.00082 1.06406 0.219168 6.68743 1.90023 6.68743

15.6653 223.158 13.6095 1.25381e-8 -18.1945 1.25381e-8Sklar's theorem can be used the other way around (from the marginal space to the unit hypercube): this is, for example, what the pseudo() function does, computing ranks.

Distributions.jl provides the product_distribution function to create independent random vectors with given marginals. product_distribution(args...) is essentially equivalent to SklarDist(IndependentCopula(d), args), but our approach generalizes to other dependence structures.

Copulas are bounded functions with values in [0,1] since they correspond to probabilities. But their range can be bounded more precisely, and [10] gives us:

For all

where

The function MCopula(d) and WCopula(2).

The upper Fréchet-Hoeffding bound corresponds to the case of comonotone random vector: a random vector

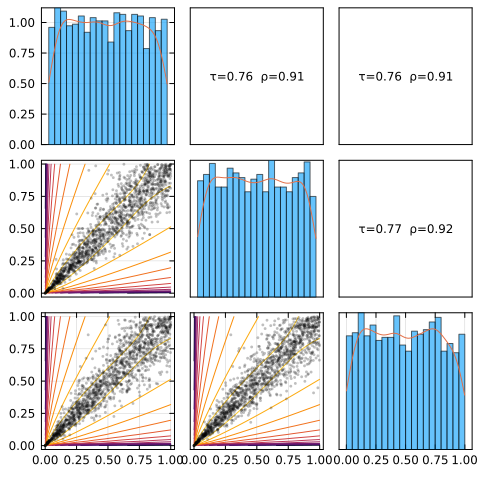

Here is a plot of the independence, a positive dependence (Clayton), and the Fréchet bounds in bivariate cases. You can visualize the strong alignment for M and the anti-diagonal pattern for W.

p1 = plot(IndependentCopula(2), title="IndependentCopula(2)")

p2 = plot(ClaytonCopula(2, 3.0), title="ClaytonCopula(2, 3.0)")

p3 = plot(MCopula(2), title="MCopula(2)")

p4 = plot(WCopula(2), title="WCopula(2)")

plot(p1,p2,p3,p4; layout=(2,2), size=(800,600))

Since copulas are distribution functions, like distribution functions of real-valued random variables and random vectors, there exists classical and useful parametric families of copulas (we already saw the Clayton family). You can browse the available families in this package in the Bestiary. Like any families of random variables or random vectors, copulas are fittable on empirical data.

A tour of the main API

The public API of Copulas.jl is quite small and easy to expose on a simple example, which is what we will do right now.

Copulas and SklarDist

The most important objects of the package are of course copulas as sklar distributions. Both of these objects follow the Distributions.jl's API, and so you can construct, sample, and evaluate copulas as standard Distributions.jl objects:

using Copulas, Distributions, Random, StatsBase

C = ClaytonCopula(3, 2.0)

u = rand(C, 5)

Distributions.loglikelihood(C, u)4.027995257604113X₁, X₂, X₃ = Gamma(2,3), Beta(1,5), LogNormal(0,1)

C2 = GumbelCopula(3, 1.7)

D = SklarDist(C2, (X₁, X₂, X₃))

rand(D, 3)

pdf(D, rand(3))5.661469705639546e-6Basic dependence metrics.

Basic dependence summaries available on copulas, whatever their dimension d:

multivariate_stats = (

kendall_tau = Copulas.τ(C),

spearm_rho = Copulas.ρ(C),

blomqvist_beta = Copulas.β(C),

gini_gamma = Copulas.γ(C),

entropy_iota = Copulas.ι(C),

lower_tail_dep = Copulas.λₗ(C),

upper_tail_dep = Copulas.λᵤ(C)

)(kendall_tau = 0.5, spearm_rho = 0.6822338331574409, blomqvist_beta = 0.19419223902606517, gini_gamma = 0.5239426802975992, entropy_iota = -0.9637828011396714, lower_tail_dep = 0.5773502691896257, upper_tail_dep = 0.0)The same functions have dispatches for u::Abstractmatrix of size (d,d) where d is the dimension of the copula and n is the number of observations, which provide sample versions of the same quantities. Moreover, since most of these statistics are more common in bivariate case, we provide the folllowing bindings for pairwise matrices of the same dependence metrics:

StatsBase.corkendall(C)

StatsBase.corspearman(C)

Copulas.corblomqvist(C)

Copulas.corgini(C)

Copulas.corentropy(C)

Copulas.corlowertail(C)

Copulas.coruppertail(C)3×3 Matrix{Float64}:

1.0 0.0 0.0

0.0 1.0 0.0

0.0 0.0 1.0and of course once again the same functions dispatch on u::Abstractmatrix, but, for historical reasons, they require dataset to be (n,d)-shaped and not (d,n), so you have to transpose.

Measure function

A measure function gives the measure of hypercubes from any copula as follows:

Copulas.measure(C, (0.1,0.2,0.3), (0.9,0.8,0.7))0.27586746224441333Subsetting (working with a subset of dimensions)

Extract lower-dimensional dependence without materializing new data:

S23 = subsetdims(C2, (2,3)) # a bivariate copula view

StatsBase.corkendall(S23)2×2 Matrix{Float64}:

1.0 0.411765

0.411765 1.0For Sklar distributions, subsetting returns a smaller joint distribution:

D13 = subsetdims(D, (1,3))

rand(D13, 2)2×2 Matrix{Float64}:

1.41983 0.128844

1.00023 0.288662Conditioning (conditional marginals and joint conditionals)

On the uniform scale (copula): distortions and conditional copulas are provided:

Dj = condition(C2, 2, 0.3) # Distortion of U₁|U₂=0.3 when d=2

Distributions.cdf(Dj, 0.95)0.9896065697045947On the original scale (Sklar distribution):

Dc = condition(D, (2,3), (0.3, 0.2))

rand(Dc, 2)2-element Vector{Float64}:

1.457043991260875

2.742608160612362And rosenblatt transfromations of the copula (or sklardist) can be obtained as follows:

u = rand(D, 10)

s = rosenblatt(D, u)

u2 = inverse_rosenblatt(D, s)

maximum(abs, u2 .- u) # should be approx zero.9.547918011776346e-14These transformation leverage the conditioning mechanismes.

Fitting (copulas and Sklar distributions)

You can fit copulas from pseudo-observations U, and Sklar distributions from raw data X. Available methods vary by family; see the fitting manual for details.

X = rand(D, 500)

M = fit(CopulaModel, SklarDist{GumbelCopula, Tuple{Gamma,Beta,LogNormal}}, X; copula_method=:mle)────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────

[ CopulaModel: SklarDist ] (Copula=Archimedean d=3, Margins=(Gamma, Beta, LogNormal))

────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────

Copula: Archimedean d=3

Margins: (Gamma, Beta, LogNormal)

Methods: copula=mle, sklar=ifm

Number of observations: 500

────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────

[ Fit metrics ]

────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────

Null Loglikelihood: -1638.2407

Loglikelihood: -1304.8881

LR (vs indep.): 666.71 ~ χ²(1) ⇒ p = <1e-16

AIC: 2611.776

BIC: 2615.991

Converged: true

Iterations: 3

Elapsed: 0.045s

────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────

[ Dependence metrics ]

────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────

Kendall τ: 0.4304

Spearman ρ: 0.6002

Blomqvist β: 0.1311

Gini γ: 0.4539

Upper λᵤ: 0.4173

Lower λₗ: 0.0000

Entropy ι: -0.6683

────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────

[ Copula parameters ] (vcov=hessian)

────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────

Parameter Estimate Std.Err z-value p-val 95% Lo 95% Hi

θ 1.7555 0.0439 40.004 <1e-16 1.6695 1.8415

────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────

[ Marginals ]

────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────

Margin Dist Param Estimate Std.Err 95% CI

#1 Gamma α 2.1205 0.1250 [1.8755, 2.3655]

θ 2.8686 0.1907 [2.4949, 3.2423]

#2 Beta α 0.9715 0.0541 [0.8654, 1.0775]

β 4.8205 0.3262 [4.1811, 5.4598]

#3 LogNormal μ -0.0175 0.0449 [-0.1055, 0.0706]

σ 1.0046 0.0318 [0.9422, 1.0670]A shortcut allows to directly get the fitting object (copula or sklardist) by simply ommiting the first CopulaModel argument:

U = pseudos(X)

Ĉ = fit(GumbelCopula, U; method=:itau)

Copulas.τ(Ĉ)0.4240184837401018Notes:

fitchooses a reasonable default per-family; passmethod/copula_methodto control it.Common copula methods include

:mle,:itau,:irho,:ibeta; for Sklar fitting,:ifm(parametric CDFs) and:ecdf(pseudo-observations) are available.CopulaModelimplements model stats:nobs,coef,vcov,stderror,confint,aic/bic,nullloglikelihood, and more.For a Bayesian workflow over Sklar models, see the examples section.

The Distributions.jl documentation states:

The fit function will choose a reasonable way to fit the distribution, which, in most cases, is maximum likelihood estimation.

We embrace this philosophy: from one copula family to another, the default fitting method may differ. Treat fit as a quick starting point; when you need control, specify method/copula_method explicitly.

Next steps

The documentation of this package aims to combine theoretical information and references to the literature with practical guidance related to our specific implementation. It can be read as a lecture, or used to find the specific feature you need through the search function. We hope you find it useful.

The package contains many copula families. Classifying them is essentially impossible, since the class is infinite-dimensional, but the package proposes a few standard classes: elliptical, archimedean, extreme value, empirical...

Each of these classes more or less corresponds to an abstract type in our type hierarchy, and to a section of this documentation. Do not hesitate to explore the bestiary !

References

H. Joe. Multivariate Models and Multivariate Dependence Concepts (CRC press, 1997).

U. Cherubini, E. Luciano and W. Vecchiato. Copula Methods in Finance (John Wiley & Sons, 2004).

R. B. Nelsen. An Introduction to Copulas. 2nd ed Edition, Springer Series in Statistics (Springer, New York, 2006).

H. Joe. Dependence Modeling with Copulas (CRC press, 2014).

J.-F. Mai, M. Scherer and C. Czado. Simulating Copulas: Stochastic Models, Sampling Algorithms, and Applications. 2nd edition Edition, Vol. 6 of Series in Quantitative Finance (World Scientific, New Jersey, 2017).

F. Durante and C. Sempi. Principles of Copula Theory (Chapman and Hall/CRC, 2015).

C. Czado. Analyzing Dependent Data with Vine Copulas: A Practical Guide With R. Vol. 222 of Lecture Notes in Statistics (Springer International Publishing, Cham, 2019).

J. Größer and O. Okhrin. Copulae: An Overview and Recent Developments. WIREs Computational Statistics (2021).

A. Sklar. Fonctions de Repartition à n Dimension et Leurs Marges. Université Paris 8, 1–3 (1959).

T. Lux and A. Papapantoleon. Improved Fréchet-Hoeffding Bounds on

-Copulas and Applications in Model-Free Finance, arXiv:1602.08894 math, q-fin. R. Kaas, J. Dhaene, D. Vyncke, M. J. Goovaerts and M. Denuit. A Simple Geometric Proof That Comonotonic Risks Have the Convex-Largest Sum. ASTIN Bulletin: The Journal of the IAA 32, 71–80 (2002).

L. Hua and H. Joe. Multivariate Dependence Modeling Based on Comonotonic Factors. Journal of Multivariate Analysis 155, 317–333 (2017).